In today’s Writing Rundown, I want to leave the brainstorming process for a bit and discuss responding to a prompt. Take a look at the prompt I used for my last Literature Spotlight, “The Blanks Left Empty”:

AP Literature Open-Ended Prompt, 1975, #2:

Unlike the novelist, the writer of a play does not use his own voice and only rarely uses a narrator’s voice to guide the audience’s responses to character and action. Select a play you have read and write an essay in which you explain the techniques the playwright uses to guide his audience’s responses to the central characters and the action. You might consider the effect on the audience of things like setting, the use of comparable and contrasting characters, and the characters’ responses to each other. Support your argument with specific references to the play. Do not give a plot summary.

Whew! That’s a lot of information to sift through. Unfortunately, many high school and college-level writing prompts are as complex, if not more so, than this one. The best thing you can do as a student is to practice parsing long prompts into pieces and figuring out how to attack them. This can and should be part of your pre-writing for any prompt-based essay, so it’s a good skill to have. So let’s go through that block of text again, carefully, and figure out exactly how to tackle this assignment.

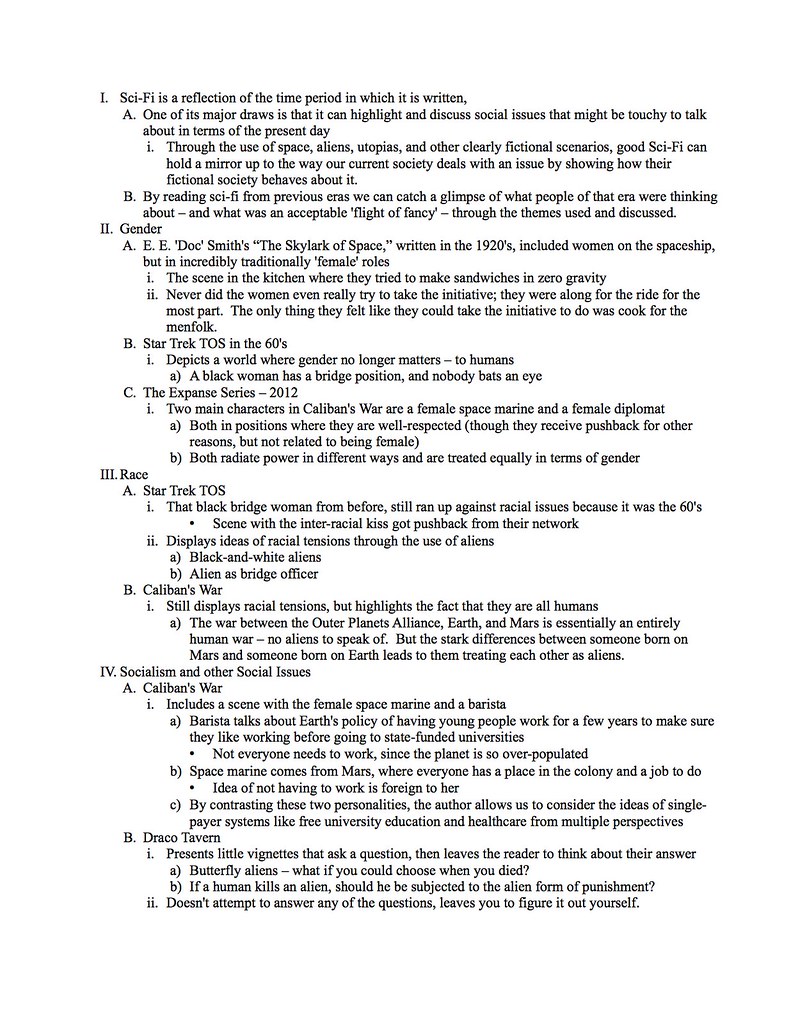

The first thing I do when confronted with a prompt this long is to scan through the whole thing and highlight, circle, underline, or otherwise mark any specific instructions the prompt gives. A specific instruction is a word or phrase that indicates a concrete thing they want to see you do in your paper. For this prompt, here’s what I’ve got after that stage:

AP Literature Open-Ended Prompt, 1975, #2:

Unlike the novelist, the writer of a play does not use his own voice and only rarely uses a narrator’s voice to guide the audience’s responses to character and action. Select a play you have read and write an essay in which you explain the techniques the playwright uses to guide his audience’s responses to the central characters and the action. You might consider the effect on the audience of things like setting, the use of comparable and contrasting characters, and the characters’ responses to each other. Support your argument with specific references to the play. Do not give a plot summary.

Okay, let’s go through those points one by one and sort out what they mean for our paper.

Select a play you have read

Fairly straightforward here. If we were given this prompt in the context of an English Lit class, it might specify which play we should be using – usually the one the previous unit centered around. But this is an open-ended prompt, so they’re keeping it more general. The important thing, though it seems obvious, is that you have to have read the play in question. Ideally, you will have read it recently enough to remember it well, and you should have a print copy of the play with you while you write, to cite page numbers for your examples. Don’t make the mistake of trying to write a convincing essay about a play you either haven’t actually read, or haven’t read recently enough to remember well. You’ll only bring yourself an unnecessary headache.

In my case, I immediately went to Assassins as one of my favorite plays, but I kept a few other play ideas in my back pocket just in case this first one didn’t work out. Second-choices for me included Death of a Salesman and Waiting for Godot, but I thought Assassins would be a more fun essay to write, so I started there.

The next highlighted instruction is the big one, the actual ‘prompt’ part of the text:

explain the techniques the playwright uses to guide his audience’s responses to the central characters and the action.

There’s a lot in this sentence, so it bears thinking about a bit more carefully. Let’s break it down even further:

explain the techniques the playwright uses

Okay, so this is going to be an essay about the craft of playwriting – the ways the author creates the story on a structural and artistic level. We’re not so much talking about the themes and symbolism within the story, as often happens with English essays, as we are talking about what stylistic tools the playwright uses to create those symbols and themes. This is going to be a nuts-and-bolts essay, rather than a narrative exploration essay.

to guide his audience’s responses

All art is about creating a response in the audience in some way – whether that’s an emotional response that causes you to cry at the end of The Fault in Our Stars, or the interminable boredom of the first half of The Good Earth, or the tense fear created through the suspense of not knowing Dracula’s specific movements for most of the novel. So here we’re talking about how the playwright can control what responses his audience experiences – how does he get us to feel that profound sadness and grief that makes us cry rather than the fear that would make us scream? So now our technical discussion has an angle – we’ll only be looking at techniques and tools that help to bring out emotional responses. If an example wants a place in our essay, it has to fit into that criteria.

to the central characters and the action.

This little tail might get overlooked if we’re not careful, but it does bear keeping an eye on. Here we’re refining the criteria for our examples – not just a tool that brings out an emotional response, but one that brings out a response relating to the characters or their actions. We’re talking about character development here, rather than plot points that are entirely out of the characters’ hands. That awesome example you have about the thunderstorm that symbolizes the relationships between the main characters? That should only be included in this essay if it actually shapes our perception of those characters moving forward – if it makes us think about those characters in a different way.

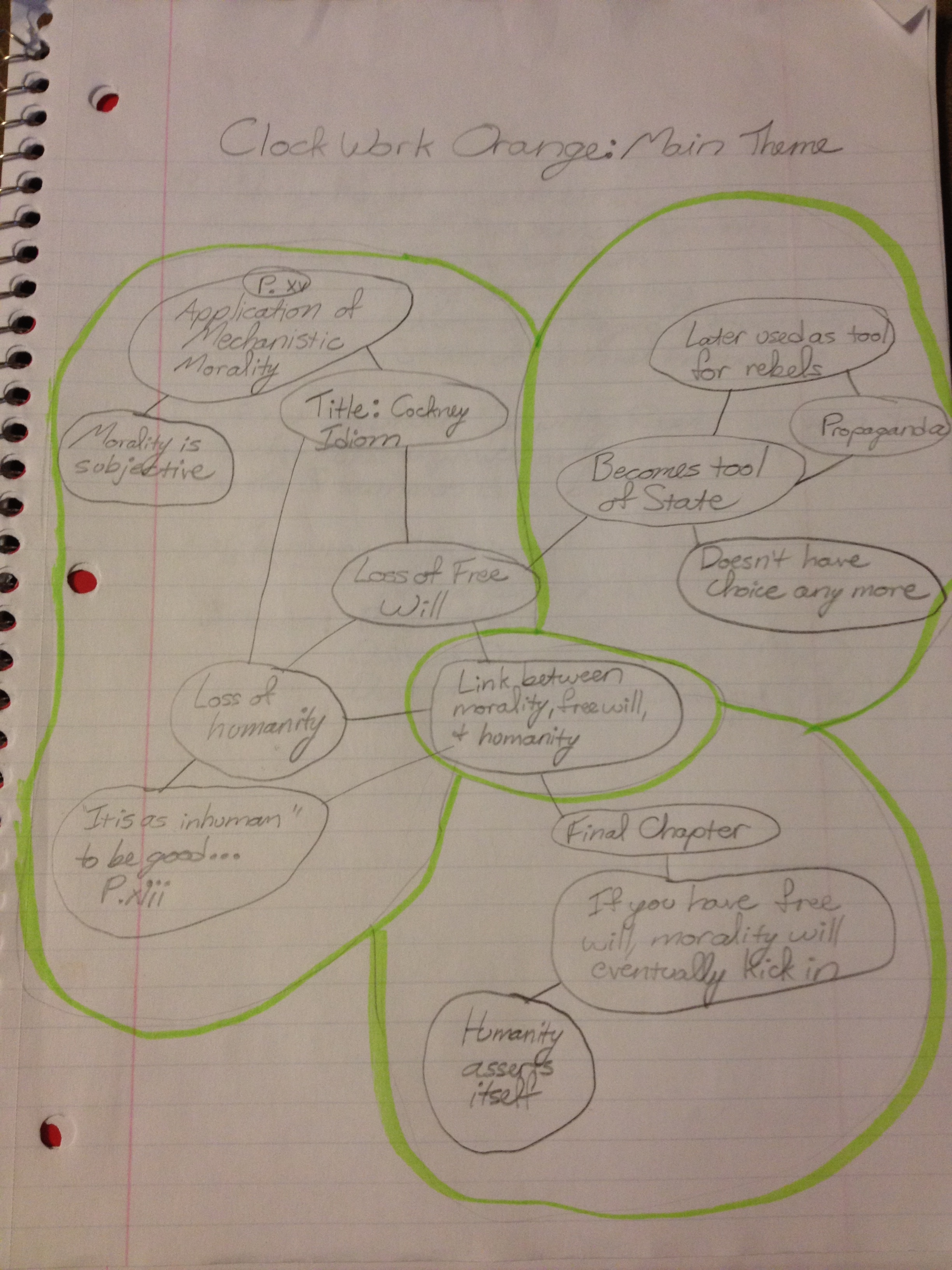

If you have an awesome example in mind that doesn’t seem to fit, take some time with it and see if you can make it fit these criteria with a little love. A word cloud can be helpful for this kind of pre-writing – the thunderstorm I mentioned above, from my Wuthering Heights essay, clarified as the central theme of my response only AFTER quite a bit of turning it around as it related to the other points I was making.

So already we’re starting to see the type of essay we’ll be writing – a very technically-focused piece about the playwright’s craft in character development. We’ll be using one play as our lens to focus this broad topic into something workable, and this is where the last two highlighted portions come in:

Support your argument with specific references to the play.

Do not give a plot summary.

These are both good things to keep in mind as we write, as they often get lost in the shuffle.

Specific examples

We’ll need to have some exact quotes and some summarized examples, but we should be able to point to specific aspects of the play to support our arguments. When pre-writing, wether with a word cloud, outline, or some other method, if it doesn’t have at least one example from the play, discard it!

Do not give a plot summary.

This one is important as a way to let your teacher know that you actually read the prompt. It’s very tempting to start off an essay by explaining the plot – you want the reader to come to the work from the same place you do, after all. Right? Well, actually, in a situation like this, it’s better to assume the reader is familiar with your subject material already. If you were in an English Lit class, the teacher would be, and even in an open-ended prompt like this, you very rarely need to know the detailed ins and outs of the plot to understand the writing techniques you’ll be discussing. All a plot summary does is eat up a paragraph or two of your (probably tight) word or page count, making it harder to fit the actual meat of your essay into the rest of your space.

This point was easy for me to hit because Assassins doesn’t really have a plot in the first place – it’s quite abstract as musicals go. All I gave in the way of summary in my essay was a single sentence to explain the theme of the play – “Assassins, which is based on an idea by Charles Gilbert, Jr., is an abstract musical centered around the men and women who, over the years, have killed or tried to kill the President of the United States.” I went on to explain the central theme of the play in a bit more detail, but only because the rest of my essay hinged on articulating how the playwright’s tools ‘guide the audience’s response’ to the central theme as it relates to the characters. Assassins is a very character-driven play in the first place, so that made it a perfect choice for this essay.

And that brings me to another important point – when you’re fortunate enough to be able to choose your own subject material, choose carefully. Pick a play that will support the type of essay you need to write intrinsically, so that you don’t end up fighting with your examples to make them stay on topic. For me, an abstract musical was an obvious choice for this one, since musicals tend to involve more suspension of disbelief for the audience, and the more abstract the staging, the easier it would be to point to the tools used.

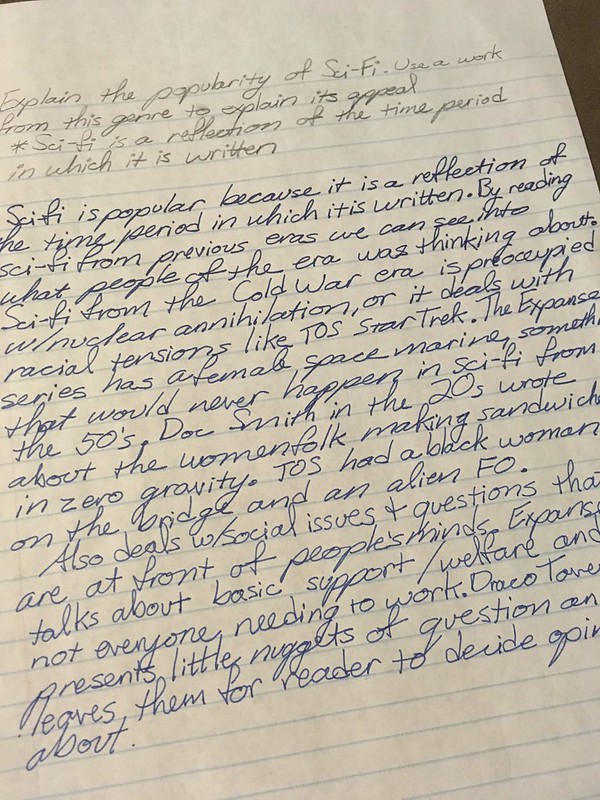

So this gives us enough of a sense of what kind of essay we’re writing to begin some pre-writing proper, using any of the techniques we’ve talked about already. For this one, I used some sketchy outlining to get my thoughts in order. And now we need to add one more piece to the puzzle – this one is one that I often add in after I have a basic outline going. You may have noticed that I skipped one sentence of the prompt when I first tackled it above:

You might consider the effect on the audience of things like setting, the use of comparable and contrasting characters, and the characters’ responses to each other.

This type of sentence is VERY important whenever it appears in a prompt. Starting off a sentence with the phrase “You might consider” makes it sound like this is an optional step, something to get you going if you need it, but often this is the teacher’s way of telling you what they’ll be looking for in your paper when grading. It’s always a good idea to try to address as many of these example ideas in your paper as you possibly can – as long as you can find some examples from your source material.

In our case, this means the paper should focus its supporting arguments on three specific playwriting tools: setting, comparing and contrasting characters, and the way the characters respond to each other. When I went to revise my outline, I started with a body paragraph for each of these tools and refined from there. My final paper included a discussion of ‘limbo’ (setting), the use of limbo to show parallel and contrasting aspects of the different characters’ stories without them showing each other (comparable and contrasting characters), and the way the assassins interact with the Balladeer (the way the characters respond to each other). Once these three were addressed, I was free to include any extra examples I wanted – in my case, a paragraph about the importance of direction as a tool and the different audience response caused by making one small directing choice that differed from the script as written.

So there we have it – a pretty decent handle on the type of essay we’re going to write, the angles we’re going to come at it from, and the specific examples we want to include. Finish up your outline, and get writing!