Last week in my Literature Spotlight, I discussed the idea of science-fiction as a reflection of the time period in which it was written. For this week’s Writing Rundown, let’s take a look at my brainstorming process.

As I mentioned in this blog post, there are many ways to brainstorm for a project. For this one, I decided to use a technique I hardly ever use myself: free-writing. Free-writing is a great tool for projects for which you have the beginnings of a lot of ideas bouncing around in your head, but none are quite fleshed out enough for you to contemplate their connections. It generally requires another form of prewriting such as a word cloud or outline to get it into a state that helps you write the essay, but it’s a great place to start.

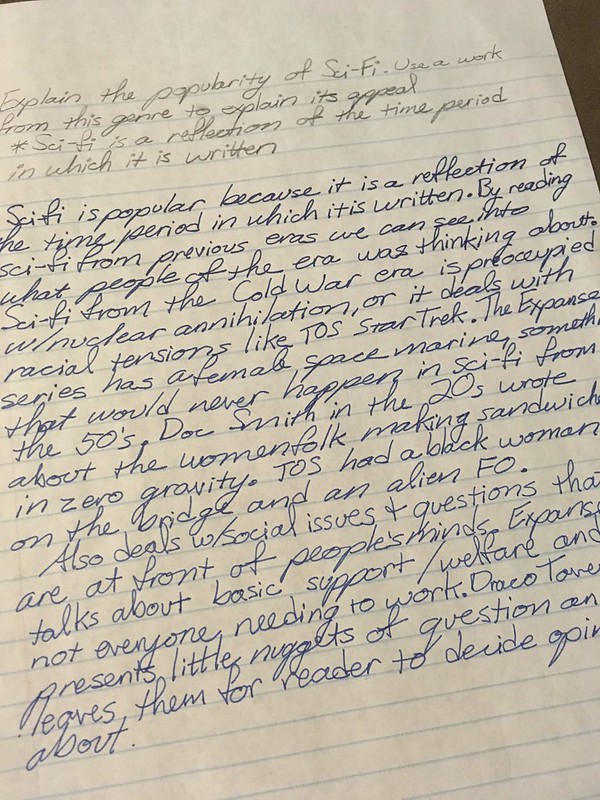

So, as a brief recap: in freewriting, sometimes called “stream-of-consciousness” writing, you put your pen down on a blank piece of paper and just start writing – and you don’t stop writing for at least ten or fifteen minutes. Jot down everything that comes to mind, trying to stay on topic but not worrying if you stray. The important thing is that the pen should never stop moving – just write down everything that comes into your head. I’ve inserted the results of my freewriting below, transcribed for the web:

Sci-fi is popular because it is a reflection of the time period in which it was written. By reading sci-fi from previous eras we can see into what people of the era was thinking about. Sci-fi from the cold war era is preoccupied w/nuclear annihilation, or it deals with racial tensions like TOS Star Trek. The Expanse series has a female space marine, something that would never happen in sci-fi from the 50’s. Doc Smith in the 20’s wrote about the womenfolk making sandwiches in zero gravity. TOS had a black woman on the bridge and an alien FO. Also deals w/social issues and questions that are at front of people’s minds. Expanse talks about basic support/welfare and not everyone needing to work. Draco Tavern presents little nuggets of question and leaves them for reader to decide opinion about.

As you can see, it’s a bit of a jumbled mess – the tenses are all screwed up, most of the sentences are fragments, and it jumps topics all over the place. But if you look closely, all of the concepts from my essay last week are there. I used my ten minutes of free-writing to tease out all of my thoughts about the topic, as well as get an idea of which works from the genre I wanted to use. You’ll see a few things that didn’t make it into the essay, like the mention of nuclear annihilation – my brain connected that in the moment, but upon re-organizing into an outline, I realized that I was taking that idea mostly from japanese animation and didn’t have any specific works to cite as evidence. So I decided to leave it out.

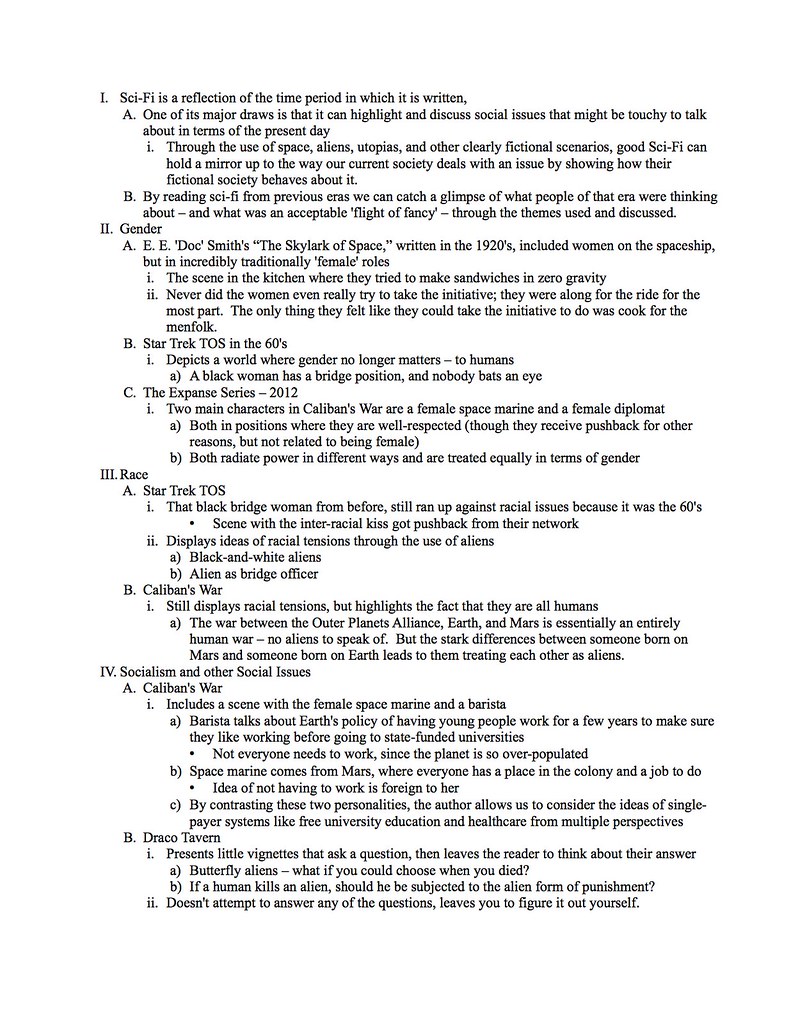

Speaking of outlines, here’s what the outline I created from that prewriting looks like:

Now, this outline didn’t start this full; this is after a few minutes of adjusting and reorganizing. I realized in creating the outline that I specifically wanted to talk about social issues reflected through the use of aliens and spaceships, so I re-organized the flow of my essay from paragraphs centered around individual works of sci-fi to paragraphs centered around types of social issues represented. In particular, the free-writing helped me realize the connection between the utopian racial ideas within the human race in TOS Star Trek and the tension between the humans and the aliens, which in turn gave me the central idea of the essay – that using aliens to represent “the other” can help throw social issues into stark relief.

And as a little bonus, here’s a picture of my actual physical free-writing page. Check out how scribbly it is – that’s how you know I was writing fast!